Written by Rose Dawson, Sea Trust Intern

Image from the National Lottery Heritage Fund (2020) showing a Puffin on Skomer Island.

My first encounter with Welsh marine life was on a small boat skipping past Skomer Island’s cliffs, age 10 with my family, while visiting St Brides across the bay. To my amazement, Puffins whirred overhead in massive numbers, seals bloomed in the swell of the waves, and dolphins skipped in the wake of the boat, making the place feel incredibly alive. Back then, I thought Skomer was just a place where wildlife gathered by chance, for tourists to enjoy. But Skomer’s wildlife doesn’t just exist here by chance, it prospers because science, careful policy and numerous citizen science projects have worked in tandem to protect the tranquillity and naturality of this physical location that so successfully draws wildlife in in its numbers.

First, for those who are not familiar with Skomer Island, it is 2.9 square kilometre island situated on the South side of St. Bride’s Bay in Pembrokeshire, just across the fast-flowing Jack Sound. Its name is derived from its novel Viking name “Skalmey”, referring to the fact that the island appears to be cut into two, joined only by a narrow piece of land called The Isthmus. Skomer originally became an Island when it was cut off from the mainland around 12,000 years ago, following a period of sustained sea level rise called the Holocene Epoch, and originally was used for farming and has a long history of human settlement dating back to the medieval ages. Now, the Island is famous worldwide for the healthy populations of diverse species that breed and feed in its surrounding waters, but that richness isn’t random; it is driven by various physical factors.

Image from the Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales (2025) showing Skomer Island in the sunshine.

The foundations of Skomer’s abundance

First and foremost, we must credit arguably one of the most important factors in moulding Skomer into the successful ecosystem it is today; the shape and composition of the seabed in surrounding waters. Skomer’s intense surrounding bathymetry – specifically reefs and deep gullies – play a major role in dictating the type of underwater environment that is found here. Deep and narrow channels that surround the island, like Jack, Broad and Little Sound, create strong tidal currents which strengthen in narrow passages, continuously stirring up nutrients like Nitrogen and Phosphorous, concentrating plankton, and collecting large numbers of fish as water moves in tide races and rips. Most notably, headland fronts and Eddies, otherwise known as the “island wake” around Skomer, create vast supplies of bait to predators. Jack Sound for instance, is only about 800m wide, and funnels tides between the mainland and Skomer. During Spring tides, the speed of this water flows exceptionally fast, exceeding six or seven knots at times, throwing up rips, overfalls and sometimes short-lived whirlpools in Skomer’s surrounding waters. Where that racing water peels away from the headlands, it causes Eddies to emerge, and along these boundaries, plankton and small fish get concentrated and pushed into bait balls, meaning that Harbour Porpoise, Common and Bottlenose Dolphins and Gannets patrol these patches because their prey is both predictable and replenished during every turn of the tides. This is like a reliable dinner bell for cetaceans and seabirds, so predators stay in the area all year-round.

Image from George Karbus Photography (2015) showing Common Dolphins next to bait ball.

Image from National Geographic Society (2022) showing plankton under a microscope.

This and Skomer’s position at the crossroads of warmer and colder ocean currents, where warmer Gulf Stream waters and cooler ocean currents from the north collide, create rare conditions, suitable for both northern and southern species. Notably, southern species normally found in warmer seas, like Pink Sea Fan coral (Eunicella verrucose) and Gold Cup corals (Tubastrea faulkneri), thrive at their northern limits here, while creatures of colder waters like the bright Sunstar starfish (Crossaster papposus) reach their southern-most ranges. This creates a spectacle where species not usually found in UK waters are present for the public to see because conditions are just right, with plentiful nutrients, all combined with that mixture of warm and cooler waters that manufactures stable habitats. Particularly, seagrass meadows like Eelgrass (Zostera marina), which act as crucial nurseries for numerous fish and benthic species, support over a third of all British Seaweed species, more than 100 different sponges and 40 different species of anemones and many soft coral species, making them one of the most diverse and benthically important plants in the UK. This means that the population is protected in the area as a feature of Skomer’s Marine Conservation Zone management plan, with its distribution and health regularly monitored.

Furthermore, life is not only fuelled around Skomer by a constant stir-up of currents and nutrients, but also by the natural world’s largest driver of energy – light. Because the waters around the island are clearer than many other UK locations due to low existing levels of pollution, sunlight can effectively penetrate into deeper water. This means that the process of photosynthesis – where plants, algae, and some bacteria use sunlight to turn carbon dioxide and water into energy-rich sugars and release oxygen as a by-product – can occur efficiently upon the seabed, keeping native seagrass meadows and kelp forests healthy, exemplifying their housing abilities. These meadows flourish on sheltered sand and gravel beds, providing a safe area where fish, crustaceans and countless other species are able to graze, hunt, and shelter from predators; supported by strong tidal flows. While healthy, these habitats will provide food and shelter for numerous small benthic species, which in turn support bigger fish, mammals and birds higher up the food chain. Together, these conditions keep the habitats that power the base of the food-web well-supported, powering a healthy ecosystem from the bottom-up.

Finally, Skomer’s Geology is the final piece of the puzzle. Skomer is made from almost entirely ancient volcanic rocks (known as the Skomer Volcanic Group to Geologists), dated to the early Silurian period. The tough, variable geology that emerges from a mixture of hard basalts and rhyolites, means that Skomer is home to a mixture of cliff environments, caves, pebble beaches and burrow-friendly soil that seabirds and seals need to nest and breed, thus adding to the physical foundation of Skomer’s appeal that brings in so many species.

Who basks in Skomer’s waters?

So, enough about why animals live here, let’s get into what lives here.

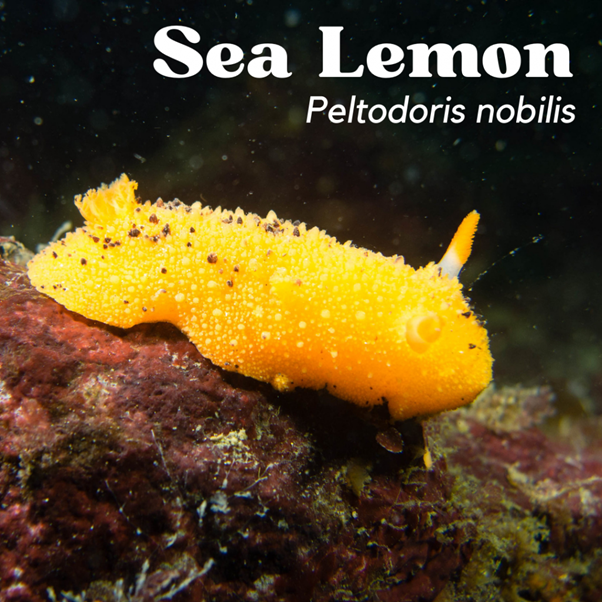

Opening the scene is a rich benthic community that thrives on rocky reefs and sandy seabed environments. An amazing 132 sea sponge species cover underwater rocks, filter feeding by pumping seawater through their bodies to extract food particles from the surrounding water. Their abundance keeps the water clear, while also providing small habitat nooks for other creatures like brittle stars, squat lobsters and juvenile fish. Eye-catching nudibranchs – colourful sea slugs – are also found here. Namely, the yellow Doris Pseuoargus, a “sea lemon” looking sea slug that grazes on the sponges that lie below and competes with anemones such as the Dahlia anemone (Urticina feline) for rock space and the strongest flow positions. Also, sponges overtop their neighbours and anemones muscle into the fastest streams to take advantage of great conditions, showing that the system is well supplied. Thanks to the Skomer Marine Conservation Zone’s long-term monitoring, scientists are actually tracking many of these benthic species very closely, noting changes like the arrival of warmer water species and the retreat of cold-water species as ocean conditions shift. Overall, Skomer’s benthic life fills a vital ecological role in the food web, providing food for more dominant and larger species and fuelling one of the UK’s most diverse underwater landscapes from the bottom-up.

Moving onto the bigger animals, Skomer and nearby Marloes Peninsula together form a core pupping area for Atlantic Grey Seals (Halichoerus Grypus), with the island’s quiet coves and caves acting as ideal breeding grounds because they offer sheltered, pebbled beaches with little disturbance under site byelaws, plus easy access to feeding grounds just offshore. This means that every autumn, dozens of female seals come ashore on Skomer’s pebble beaches to give birth, and since about 2009, there has been a steady increase in grey seal pups born here, approximately 250 pups each year; reflecting the safe and healthy allure of breeding in Skomer’s waters. Peak pupping occurs in September and October, and by early winter the pups are weaned and ready to venture into the sea, so if you’re ever in Pembrokeshire during these months, you must go and see it! Visitors to the island commonly witness scenes of plump seal pups learning to swim under the watch of their mothers, or big bull seals fighting in the surf.

Beyond seals, Harbour Porpoise (Phocoena Phocoena) and Bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus), Common (Delphinus delphis) and Risso’s Dolphin (Grampus griseus) bask in Skomer’s waters, and are frequently seen hunting for fish in the strong surrounding tidal currents. Porpoise are regularly seen year-round in small groups, with sightings peaking in the warmer months of June through October when food is abundant. These shy mammals usually reveal themselves only as a fleeting dorsal fin and a swirl of water as they chase fish like herring and whiting. Bottlenose are also present here, the larger inhabitants of the area. They are more deep-bodied, slow and deliberate predators compared to Porpoise, and are often seen travelling in small groups close to the headlands, working with the tide fronts for larger fish and will occasionally bow-ride in settled seas. On top of this, they also compete with Common dolphins which are more sleek, fast and sociable dolphins, and have an “hourglass” pattern on their flanks. They are known for swimming in conveyor belts of baitfish spun up by Jack Sound and can often be seen on local boat tours. Risso’s dolphins are arguably the outliers of the area, however. They are pale, often heavily scarred with a curved dorsal fin, and favour the deeper water off the island where they hunt squid. Together with Porpoise, they track the predictable prey patches created by Skomer’s oceanographic traits, which is why citizens see them so often. If you’re ever in the area, ensure you go out and try to spot them! Make sure to enjoy them at a respectful distance by following local protection regulations in order to keep disturbance low.

Image from Sea Trust Wales (2025) showing a Harbour Porpoise in Pembrokeshire’s waters.

Image from National Geographic (2014) showing a Bottlenose Dolphin.

Image from Sea Trust Wales (2023) website showing a Risso’s Dolphin breaching.

Moving onto the more ariel inhabitants, Skomer is arguably most famous for it’s seabird spectacles, where each year around 43,000 Atlantic Puffins return to the Island to breed – an all-time record that contests global trends of decline elsewhere in the world. The Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales, which manages Skomer, has recently reported 43,626 puffins from April to July in 2025, exceeding the previous year’s count. These comical seabirds are known as a ‘circus’ in groups and choose Skomer for its safe, predator-free nesting grounds and plentiful food. They raise their chicks in rabbit-like burrows on the slopes in mid-April, inhabiting already made rabbit burrows, and during their time here, they feed on small fish and sand eels then carry them back to their burrows. This relationship is under pressure however, as sand eels are finely tuned to cold, plankton rich waters, which climate change is knocking slightly. Consequently, adult Puffins are struggling to supply food for chicks as much as they otherwise would, meaning they must travel further for decent shoal numbers, meaning feeds per day are decreasing. To combat this, wildlife managers are doubling down on the things that keep the inshore food web intact: tightening disturbance controls during chick-rearing, enforcing boat speed/approach limits around rafts, and protecting sensitive seabed and nursery habitats under MCZ byelaws.

Finally, by day, Skomer’s cliffs also brim with razorbills and guillemots – but by night another host takes over; the Manx shearwater. An astonishing 350,000 pairs of Manx shearwater breed in burrows on Skomer– nearly seventy percent of the world’s population. In the darkness you can hear their strange, haunting calls as tens of thousands of them return from the sea, ready to one day migrate to South America. Recently, we have had many Shearwaters come to stay with us at Ocean Lab after they have blown off course or been distracted by bright tanker lights offshore. Their legs are set far-back in their body, so are not designed for walking on land, leading to them adopting a ‘shuffle’ on land; a technique that often makes them appear injured – but they-re not, just not meant to be on land! So, we have ringed many of them and released them back into the wild, where one day we hope to identify them when they return to Pembrokeshire, indicating that they have managed to rehabilitate themselves in the wild despite hardship.

Image from National geographic (2016) showing Puffins on Skomer.

Other species found here include the Strom Petrel, Kittiwakes, Fulmars, Herring, Lesser and Great Black-Backed Gulls, Raven, Buzzard, Kestrel, Short-eared Owls and various mammals such as the Skomer vole, Wood Mouse, Rabbit, Greater Horseshoe bats, and Tetrapoda like Common Lizard, Common Toad and the Palmate Newt. So, it is safe to say that Skomer is a gold mine for wildlife sightings, in and outside of the water.

How Skomer is safeguarded

Skomer’s wildlife can thrive because the island is matched by the law that guards it. Decades of layered designations – on land and at sea – give managers clear tools to reduce disturbance, protect habitats and adapt rules as new evidence comes in.

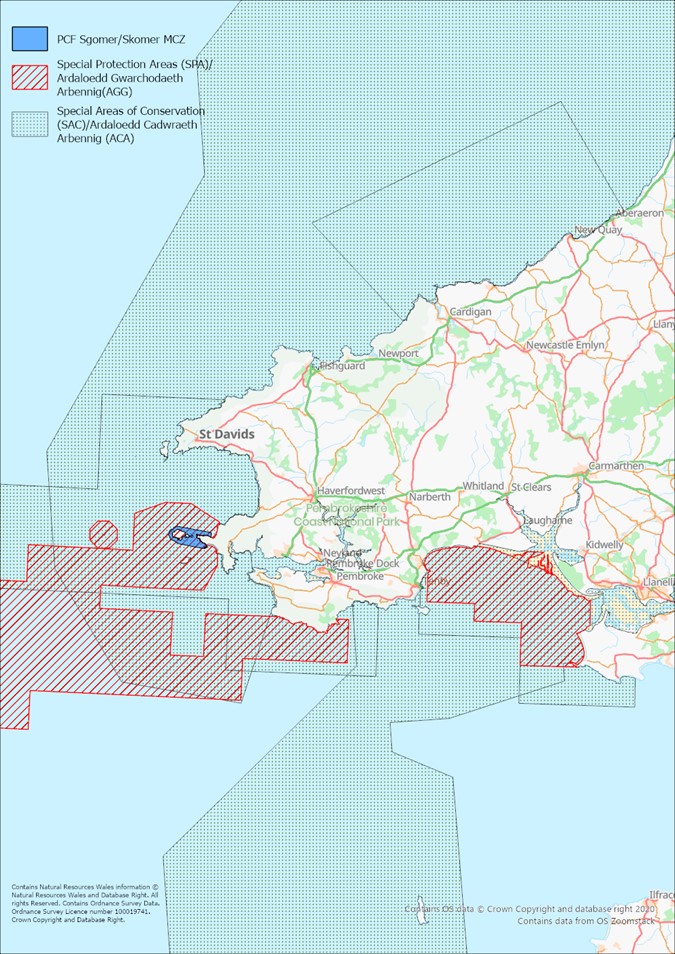

First, Skomer’s importance has long been recognised by the Welsh government. It was declared one of the country’s first National Nature Reserves under ownership of the Nature Conservancy (currently known as the Countryside Council for Wales) from 1959, and is now managed by the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. In 2014, Skomer became Wales’ first Marine Conservation Zone (MCZ) in under the Marine and Coastal Access Act of 2009, that aimed to establish a comprehensive framework for managing the marine environment through marine planning, the creation of Marine Conservation Zones to protect biodiversity, and the provision of public access to coastal areas. Skomer’s MCZ management plan uses byelaws and codes of conduct to restrict certain activities, such as dumping and mobile fishing, to safeguard its ecological value. This meant that under the act, Skomer became the only stretch of water in Wales to have a protected status under Natural Resource Wales.

Image from Pembrokeshire Marine Special Area of Conservation (2022) showing Skomer’s protections divided into a Marine Conservation Zone, Special Area of Conservation and Special Protection Area.

Cetaceans are also protected here, as it’s location overlaps with a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) that protects Harbour Porpoise specifically, due to their identification as a key, year-round species in the area. Finally, a Special Protection Area (SPA) that protects seabirds, allows for birds and their habitats to ensure that human activities do not negatively impact protected species and their environment. Generally, local protection is tied into wider UK law under the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) who work under the Welsh Government, making Skomer a benchmark for conservational success, where some of the most wonderful UK species thrive because of careful planning.

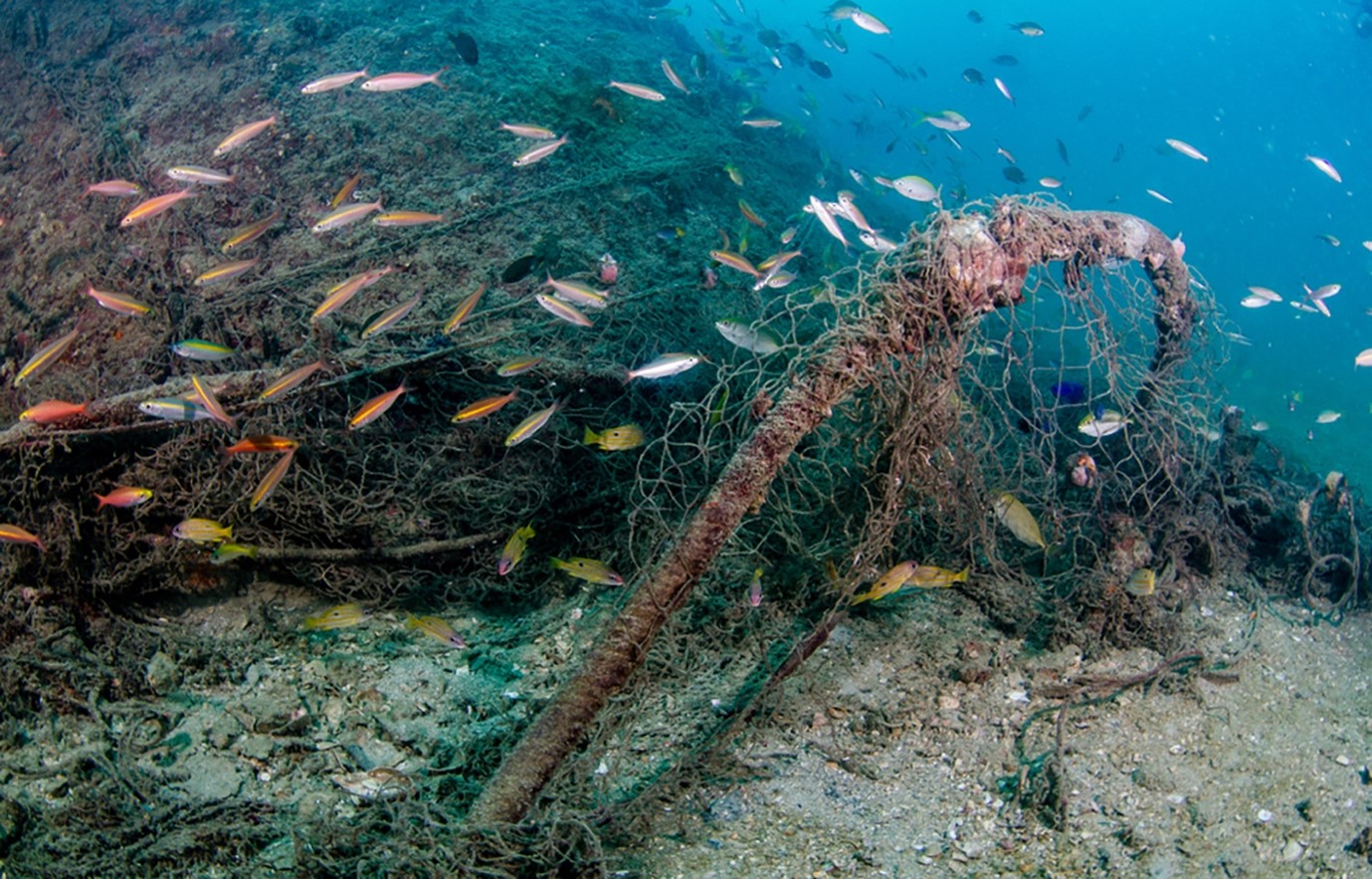

Image from Prairie (2024) showing the destruction of seafloor through bottom trawling.

One way that the MCZ byelaws protect Skomer is the law that states that activities such as dumping rubbish and taking, killing or disturbing wildlife are an offense. This has led to an enforced 5-knot speed limit within 100m of the shoreline, implemented to reduce disturbance to wildlife in the area. The Reserve also benefits from fishing restrictions, which prohibits dredging, beam trawling and the taking of certain scallop species (year 2000 onwards). Under the MCZ, biological monitoring of seabed organisms and the management of human activity take precedence, all confined to a zonal site management plan marked by buoys on the water. Under the Marine Nature Reserve designation, 1,400 hectares of seabed around Skomer and Marloes Peninsula are protected and a monitoring programme has been developed with the UK’s most comprehensive series of marine monitoring projects at a single location. Lastly, Skomer’s SAC (designated under the EC Habitats Directive in 2004) allowed for its outstanding marine life to be protected under defence of habitats and species of European importance, like the Harbour Porpoise mentioned before. The inclusion of Skomer into SACs helps protect not just birds, but marine species and habitats around the island.

There also exist controls on the on-land animals that are allowed to live on Skomer’s land. On land, Skomer is carefully managed by The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales, who ensure the prevention of invasive ground predators like rats and foxes on the island, so seabird colonies are protected from predation. Skomer is therefore one of the few places in the UK with no ground predators, allowing on-land species to thrive in immense numbers without predatory threats. Thanks to this sanctuary, Skomer and Skokholm together form one of Britain’s most important Special Protection Areas for seabirds.

Nonetheless, arguably Skomer’s greatest strength is the commitment to long-term monitoring and research. Each year many researchers visit the island, wardens, NRW and university teams count seabirds (including Puffins and Manx Shearwaters), survey Grey Seal pups, and run effort-based watches for Harbour Porpoise and dolphins, with tagging and ringing to track movements. Divers also monitor fixed reef stations, seagrass beds and sandy infauna, while loggers record tides, temperature and water quality alongside seasonal plankton tows. These datasets then feed annual condition assessments for the MCZ and drive adaptive management, like the tweaking of byelaws, zoning and visitor guidance to cut disturbance and the protection of key habitats. Volunteers all pull together to log bill-loads, report grounded birds and join standardised cetacean surveys. Such data have been invaluable in guiding management decisions, for instance, confirming the recovery of scallops, detecting drops in pink sea fans, or spotting new invasive species early. This constant level of vigilance means problems are caught early and successes are really well documented; thus, policies can be adapted based on evidence (for example, if a certain anchor point is damaging seagrass, it can be moved). Together, all of this work allows for regular ‘health’ assessments to be made of Skomer’s water and land animals, as part of one of the UK’s most intensively studied marine areas in the UK.

So, to round up, Skomer is one of the most active areas of conservation in Europe, and is a benchmark example of how citizen science, policy and natural drivers of ecosystem health can all plug together to drive the flourish of a marine zone. If you would like to get involved in the conservation of Skomer, you can help by taking part in local wildlife surveys or data-entry sessions, and by performing environmental stewardship: stick to paths, keep clear of burrows, and respect boat speed and approach rules. You can also report wildlife sightings (with date, time and location) to the West Wales Biodiversity Information Centre (WWBIC) or contact the Skomer Wardens, report any grounded seabirds to conservation charities through the appropriate local channels, and finally support projects that safeguard seagrass, reefs and long-term monitoring.

Acknowledgement of sources

Images were obtained from the following sources:

Buttivant, H. (2016). Scarlet and Gold Cup Corals -A Treasure Quest. [online] Cornish Rock Pools. Available at: https://cornishrockpools.com/2016/04/21/scarlet-and-gold-cup-corals-a-treasure-quest/ [Accessed 18 Oct. 2025].

Ionescu, A. (2022). Pink Sea Fan Corals Are Resilient to Climate Change. [online] Earth.com. Available at: https://www.earth.com/news/pink-sea-fan-corals-are-resilient-to-climate-change/.

Jackson, A. and Hiscock, K. (n.d.). MarLIN – the Marine Life Information Network – Dahlia Anemone (Urticina felina). [online] www.marlin.ac.uk. Available at: https://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/1392.

Monteray Bay Aquarium (2025). Deep Sea Sunstar. [online] Montereybayaquarium.org. Available at: https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/deep-sea-sunstar [Accessed 18 Oct. 2025].

Munnerlyn, I. (2022). Creature Feature: Sea Lemon | NEC. [online] Yournec.org. Available at: https://www.yournec.org/creature-feature-sea-lemon/ [Accessed 18 Oct. 2025].

National Geographic (2014). Bottlenose Dolphin. [online] Animals. Available at: https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/bottlenose-dolphin.

National geographic (2016). Puffin facts! [online] National Geographic Kids. Available at: https://www.natgeokids.com/uk/discover/animals/birds/puffin-facts/.

National Geographic Society (2022). Plankton. [online] education.nationalgeographic.org. Available at: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/plankton/.

National Lottery Heritage Fund (2020). Welsh Island Puffins Protected Thanks to Heritage Emergency Fund Grant. [online] The National Lottery Heritage Fund. Available at: https://www.heritagefund.org.uk/news/welsh-island-puffins-protected-thanks-heritage-emergency-fund-grant [Accessed 18 Oct. 2025].

Pembrokeshire Marine Special Area of Conservation (2022). Marine conservation in Pembrokeshire – Pembrokeshire Marine SAC. [online] Pembrokeshire Marine SAC. Available at: https://www.pembrokeshiremarinesac.org.uk/marine-conservation-in-pembrokeshire/.

Prairie, E. (2024). 10 Vessels Found Responsible for 25 Percent of Harmful Bottom Trawling in UK MPAs. [online] Seafoodsource.com. Available at: https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/environment-sustainability/10-vessels-found-responsible-for-25-percent-of-harmful-bottom-trawling-in-uk-mpas.

RSPB (2025a). Guillemot Bird Facts | Uria Aalge. [online] www.rspb.org.uk. Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/guillemot.

RSPB (2025b). Manx Shearwater Bird Facts | Puffinus Puffinus. [online] www.rspb.org.uk. Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/manx-shearwater.

RSPB (2025c). RSPB. [online] www.rspb.org.uk. Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/razorbill.

Sea Trust Wales (2023). Risso’s Dolphin Facts | Sighting Guide | Sea Trust. [online] Seatrust. Available at: https://www.seatrust.org.uk/wildlife-sightings/what-can-you-see/rissos-dolphin/ [Accessed 18 Oct. 2025].

Sea Trust Wales (2025). Pembrokeshire Wildlife | What You Can See | Sea Trust. [online] Seatrust. Available at: https://www.seatrust.org.uk/wildlife-sightings/what-can-you-see/.

Toon, A. and Getty, S. (2022). Eelgrass guide: What It Is and Why Eelgrass Meadows Are Crucial for Some Marine and Bird Life. [online] www.discoverwildlife.com. Available at: https://www.discoverwildlife.com/plant-facts/water-plants/eelgrass-guide.

Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales (2025). Atlantic Grey Seal | The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. [online] www.welshwildlife.org. Available at: https://www.welshwildlife.org/atlantic-grey-seal.

Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales (n.d.). Skomer Island Day Trips | the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. [online] www.welshwildlife.org. Available at: https://www.welshwildlife.org/skomer-island-day-trips.

WP-admin.cz webmaster (2015). Bait Ball with Common Dolphin Azores | George Karbus Photography. [online] George Karbus Photography. Available at: https://georgekarbusphotography.com/bait_ball_with_common_dolphin_azores/ [Accessed 18 Oct. 2025].

Information for this blog has been collected from various sources. Please find these sources at:

The Wildlife Trust at https://www.welshwildlife.org/nature-reserves/skomer-island-0 and

https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/marine/anemones-and-corals/pink-sea-fan and https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/marine/anemones-and-corals/dahlia-anemone and

Pembrokeshire Coast at https://www.pembrokeshirecoast.wales/things-to-do/pembrokeshires-islands/skomer/ and https://www.pembrokeshirecoast.wales/about-the-national-park/geology/

The Marine conservation Society at https://www.mcsuk.org/news/skomer-island-a-marine-conservation-success-story/

The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Seascape Character Assessment at https://www.pembrokeshirecoast.wales/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SCA25-Skomer-Island-and-Marloes-peninsula.pdf

The JNCC at https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/skomer-skokholm-and-the-seas-off-pembrokeshire-mpa/

National Geographic at https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/plankton/

The Seal Monitoring on Skomer Island Report for 2024 at https://www.welshwildlife.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/Seal%20Monitoring%20on%20Skomer%20Island%20Report%202024.pdf

The RSPB at https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/puffin and https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/razorbill and https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/guillemot and https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/manx-shearwater

The Pembrokeshire Marine Special Area of Conservation website at https://www.pembrokeshiremarinesac.org.uk/marine-conservation-in-pembrokeshire/